The Ypres Salient is a natural jump-off point for a visit to the Western Front: the scene of fighting throughout the war and a name synonymous with the savagery of the conflict – as one soldier expressed,“there is fighting, there is damned fighting, and there is the Ypres Salient” .

The Salient was formed in October 1914 when the German offensive was stopped, creating a small but bothersome 10 kilometre bulge along the 24 kilometre front line. For the opposing armies the bulge forced them to defend three flanks, the Germans having to draw reserves from crucial battles, such as Verdun, to defend their line.

Ypres is a beautiful medieval town, once the centre of the Flemish textile trade with England during the middle ages, but it was almost entirely destroyed during the First World War. And regrettably it is for its role in the war, and the consequences of that, for which Ypres is perhaps now most popularly remembered.

“I think the most interesting sight out there is the city of Ypres. A walk through it on a moonlight night gives one an impression of what the ruins of Roman architecture must look like. There have been some of the most magnificent buildings that the architects and artists of Europe could devise, built there. Chief among them is the Cloth Hall. It is an enormous building and the carving over the whole of it both exterior and interior is wonderful. At one time Ypres had a population of 200,000 but of late years it has dwindled to less than 80,000. The Cathedral is hardly less beautiful than the Cloth Hall, and practically every building has been exceptionally fine. As you probably know Ypres was the great lacemaking centre of Europe, and the Cloth Hall was for the display of the products of the city for buyers from all parts of the world” William Harry Jennings, February 1915

But despite the destruction, all but complete by the summer of 1915, the bombardment of the town continued. “The City of Ypres, is nothing but ruins, not a sound house left. The Germans shell the place night and day, but they might as well save their shells for all the good it does them.” Charlie Snazelle – June 25th, 1915

In the years immediately following the war, there was much debate as to what should be done with the desolate landscape around Ypres. As part of the post-War cleansing many thought it should be transformed in to a vast memorial. Winston Churchill wondered whether it would be possible to “acquire Ypres, either by gift from the Belgians or by some arrangement … as British property, and gather there round these ruins and make it the centre of all the burying places around…” Reflecting the religious overtone that would dominate efforts to cope with what had been lost, he suggested that ‘it would become a very great place of pilgrimage for the descendants of all those who took part in defending Ypres against all attacks.’

Members of the Belgian nobility, the Government, and even a leading architect from Belgium, supported Churchill’s idea of keeping the ruins as they were and that the local townspeople had no right to change them. In December 1919 the Belgian National Congress of Architects passed a resolution declaring against restoration of the Cloth Hall and the Cathedral: “if the British wished to rebuild the Cloth Hall and make it a museum to their national glory they should be permitted to do so.” But fortunately this sentiment did not prevail.

The rebuilding of Ypres began in the 1920’s aided, fortuitously, by architectural diagrams that had been prepared in the years leading up to the war as part of a program to renovate a number of the major buildings – the scaffolding that is seen on one of the more celebrated pictures of the burning of the Cloth Hall from 1914, was there because of the restoration work that was taking place at the time. While many of the buildings were restored to their original look, some were changed: a few the houses adopted an art deco look to them, and the shape of the spire on St. Martin’s Cathedral, as an example, was originally a square tower.

The construction began in earnest through the early twenties, and pictures from 1923 show that a good part of the Grote Market, with its dormered buildings and peaked roofs, were complete – although the area behind the market remained largely rubble. The rebuilding of the Cloth Hall took part in stages – the final part of which was not actually completed until 1967 – almost 50 years after the war had ended.

What is most striking in walking through the town today is that the buildings are so new, while its character is still medieval – from the ancient Cloth Hall to the buildings that surround the Grote market with their dormer windows, from St Martin’s Cathedral and St Georges church, to the Menin Gate itself. But despite the town’s gothic appearance the war is omnipresent.

Rather than its theme park to the War, the Intermational War Graves Commission opted to build a massive mausoleum to those who were killed in the Ypres Salient and have no known grave, The Menin Gate Memorial to the Missing; what Siegfried Sassoon called a “sepulchre of crime”. The memorial is located on the site that was the closest gate to the fighting in the area, and would have been passed by most of the men heading to the Front- although heavy shelling of this area meant that most men would actually have approached from a different gate.

The centrepiece of the memorial is the Hall of Memory, a vast archway lined with panels of Portland stone – the same as that used for headstones in the Commonwealth cemeteries, in which names of the missing

are engraved. Despite its size, the memorial can only accommodate the names of 54,900 men who went missing in the area (it was subsequently decided that it would only mark those who went missing before mid August, 1917); the names of a further 35,000 men are listed on a memorial at Tyne Cot Cemetery just West of Passchendaele, and those from Newfoundland and New Zealand are listed on a separate national memorials.

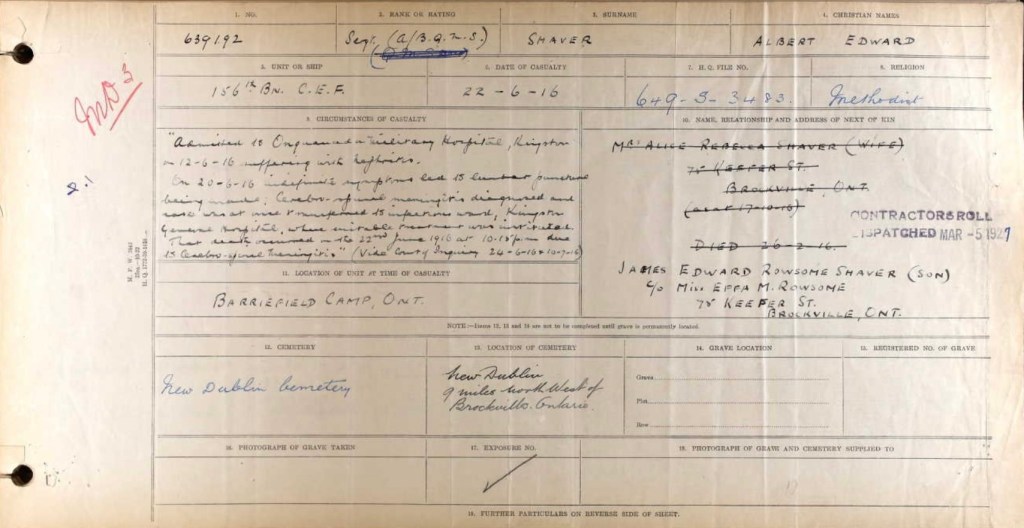

Samuel Boyd is just one of the thousands listed. One of four brothers from Limvardy, County of Londonderry, he was working in Edinburgh at the time the war broke out. Enlisting under his mother’s maiden name, he ended up in the 2nd Battalion Royal Scots and departed for France at the end of the first week of December, 1914. The battalion would spend much of the next year stationed around Ypres.

In July 1915, Boyd’s battalion was transferred to Sanctuary Wood, south of the Ypres-Menin road. The ground in front of their position rose steadily across No Man’s Land towards the German trenches a hundred yards away, and then contnueed rising towards Hooge.

On the evening of the 24th the battalion lay in their trenches around Sanctuary Wood, suffering through a steady downpour, their clothes drenched by the rain.

Shortly before 4 a.m., as a massive British and French assault started near Loos to the Southeast, a vigorous artillery barrage began around Sanctuary Wood – the prelude to a British diversionary attack that was hoped would prevent German reserves from heading south. Three British mines were detonated under the German lines opposite Boyd’s battalion and, as the ground settled 30 minutes after the bombardment had begun, they started their advance towards “Sandbag Castle”, a small hill behind the German trenches.

While the battalion quickly seized their objective, the Germans mounted a vicious counter attack that prevented them from holding the line. By the end of the day the battalion was back where it had begun the day, at the cost of 244 casualties; Samuel Boyd among them.

Today, the Menin Gate, and the Last Post ceremony which honours those killed are tourist attractions, the buglers competing with Ipods. But the names etched throughout the Arch still hold people’s attention; the imagination is exercised as arms and fingers point in their direction, and hands wear down those within reach.

Leave a comment