The use of mines as a siege weapon in war goes back many centuries when tunnels were dug under castles, filled with explosives and used to breach the walls of the fortress. Ironically, it was the medieval nature of the First World War, with static defenses, many heavily fortified in the case of the Germans, that made undergound mining a natural weapon for both sides. While the Germans, were the first to exploit the use of mines, at Festubert in December 1914, the British, Australians, New Zealanders and Canadians all developed their own tunnelling units. It soon developed in to a continuous part of the war’s daily routine, as mine tunnelling companies conducted mine-countermine operations below the trenches.

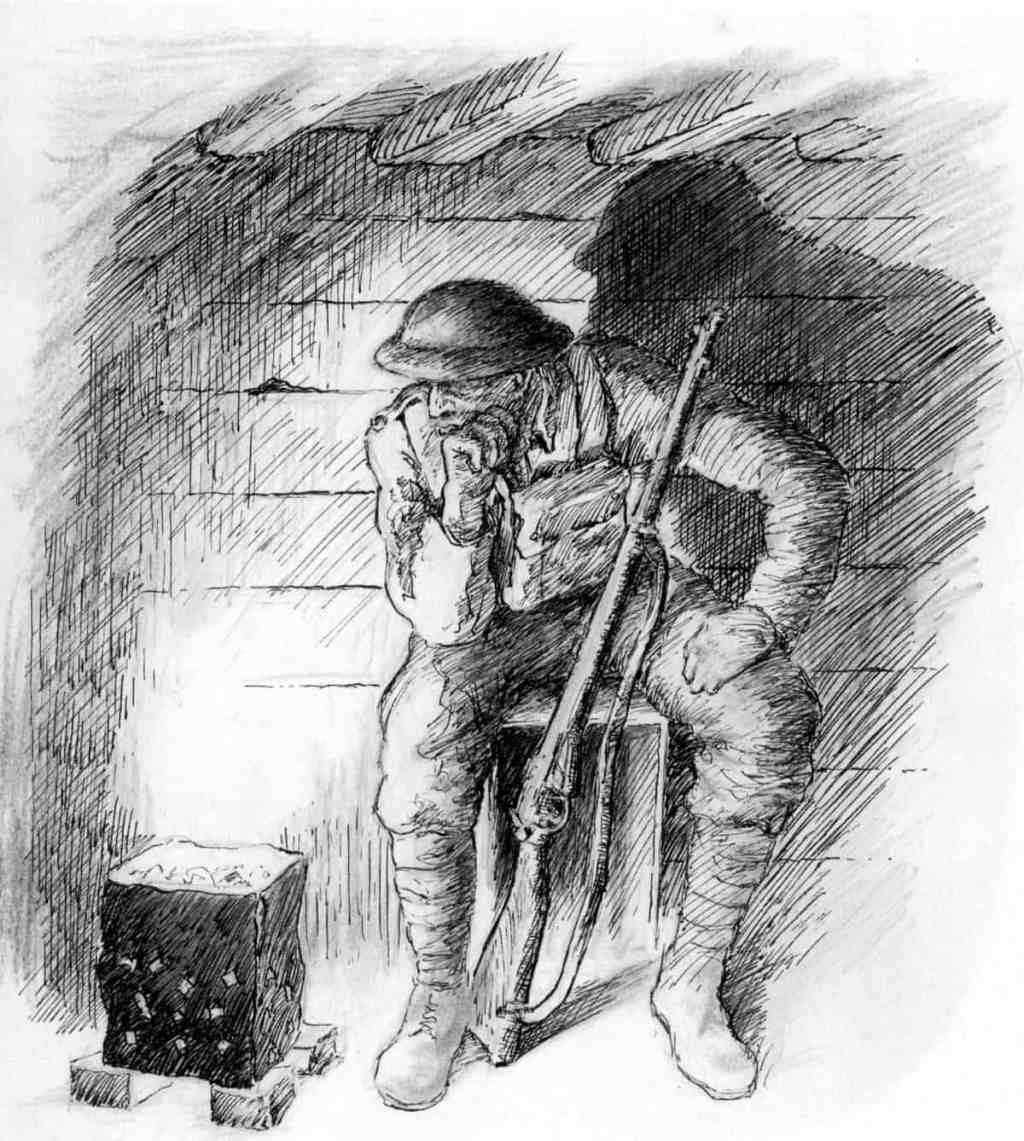

“It was no unusual occurrence when walking along these trenches to see someone stretched out flat with his ear close to the bottom of the trench, listening attentively. . . No one liked these sounds, for they meant that mining was going on underneath, and mined trenches are about as comfortable to occupy as the top floor of a burning powder plant.” Charles Savage, 5th Canadian Mounted Rifles

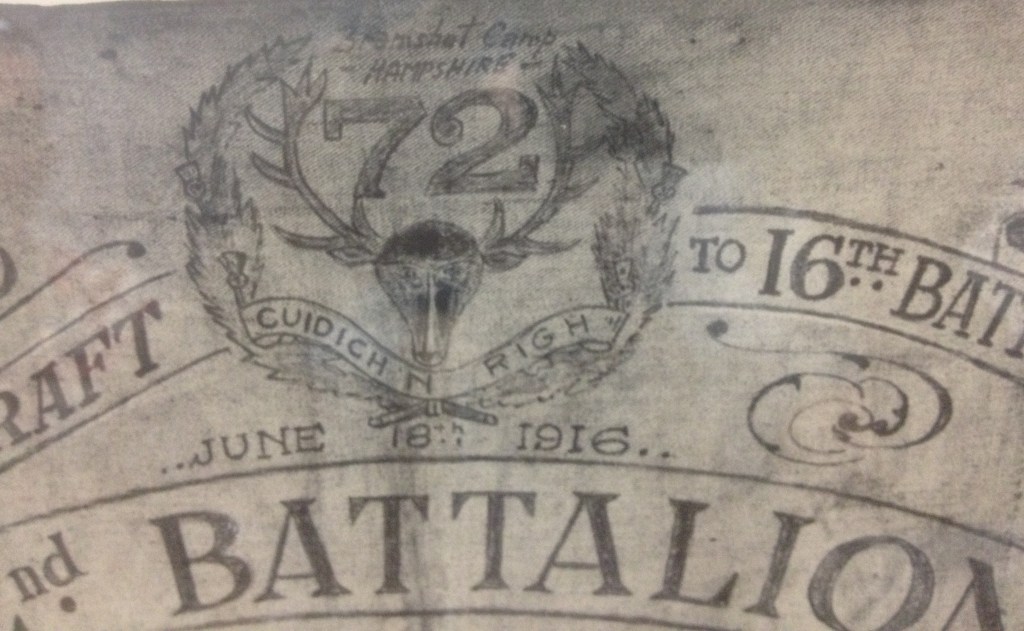

The results of mine warfare, however, were mixed. It contributed greatly to the British success at the Battle of Messines Ridge in 1917, where 21 mines were dug, some more than a year in advance of the battle. Nineteen of the mines were detonated under the high ground of the ridge to start the battle. These devastated the German lines and allowed the British to capture all initial objectives within three hours (two mines failed to detonate, though one of them did explode in a thunderstorm in 1955). The mines were laid by tunnelling companies from Britain, Australia and Canada. In the months leading up to the June 7th attack, and the days after, Canadians were heavily engaged in mining and support operations.

But in the Somme, where 19 mines were detonated on the first day, the result was very different. The largest of these was positioned around La Boisselle – the Lochnager Mine – and consisted of two charges of explosives planted fifty feet below the surface. When detonated on July 1st, the blast was reportedly heard in Whitehall. But this mine did not help the men of the 34th Division, most of whom were cut down by criss-crossing machine gun fire within minutes of leaving their trenches.

Two months after Vimy Ridge, while the Canadian Corps was approaching Lens for a planned attack on Hill 70, the 2nd Canadian Tunnelling Company was in the Ypres Salient supporting preparations for the Battle of Messines and the Third Battle of Ypres. Many of the Canadian graves in Ramparts Cemetery are those of engineers and tunnellers supporting operations in the lead up to, and after Messines Ridge. Michael Patrick Giff, Erick Kunnos and Herbert Bray are three of the Canadian soldiers – miners in the 2nd Canadian Tunnelling Company – buried in Ramparts.

Patrick Giff was a 28 year old miner, originally from Mullingar County, Ireland who enlisted in July 1916. At the time he enlisted he was living in the YMCA in Vancouver, having come to Canada via Glasgow and then New York. Arriving in New York on 15 June, 1914, he declared his intent in the District Court of New York, to “renounce forever all allegiance and fidelity to any foreign prince, particularly King George V”. Yet three years later, just four months after arriving at the Front, he was killed fighting for the King.

Another soldier in the 2nd Tunnelling Company – a farmer from Winnipeg, Erick Kunnos – was also 28 years old. Kunnos was a native of Finland who enlisted in the winter of 1915 and arrived at the 2nd on the same day as Giff, in mid February, 1917. Kunnos was killed on June 29th by shell fire at Shrapnel Corner, South of Ypres.

Herbert Bray, a 26 year old clerk from Vancouver Island, enlisted in August 1915 and joined the 2nd Tunnelling Company in October 1916. Bray was on a carrying party on the evening of June 30th, between Railway Dugouts and Lille Gate, when he was killed instantly by shell fire. He was the only man in the 2nd who was killed that day.

Like so much from the war, mines have left an indelible mark on the landscape. Whether camouflaged by woods, like the crater from the Hawthorne mine or turned in to natural ponds by the high water of Flanders, they are one more reminder of the immense destruction that took place. As General Plumer, commander of the 2nd Army reportedly said on the evening before the attack on Messines Ridge: “Gentlemen, we may not make history tomorrow, but we shall certainly change the geography.”

Leave a comment