It was a story that ran in papers across the country two weeks after the Declaration of War: “Rocky Mountain Rangers Fired on From Ambush,” read The Ottawa Journal on August 20th.

“What is believed to have been a determined attempt to wreck the troop train which passed through Revelstoke Sunday night carrying 150 sailors from the Shearwater and Algerine to the Atlantic coast to man the Niobe occurred at Mountain Creek Bridge, about 50 miles east of Revelstoke, according to news that has now reached the city.”

The Mountain Creek Bridge, measuring 164 feet high and 1,068 feet long, was the second highest bridge in British Columbia. Located three miles from the nearest settlement on either end, it was also considered one of the most vulnerable points on the railway.

On Sunday, August 16th, a warm summer evening, dark, with a waning crescent moon that cast just enough light to see, six men from the 102nd Regiment Rocky Mountain Rangers were guarding the Mountain Creek Bridge, three at either end. They had taken up the task of guarding the bridges in the area two days earlier, replacing armed Canadian Pacific Railway (CPR) constables who had been hired to guard every bridge of the CPR. The public was warned not to try to cross the bridge at night as the troops had orders to “shoot to kill”.

It is a popular belief that emotions ran high against Canadians of German descent in the days that immediately followed the Declaration of War with Germany on August 4th. There were, however, just a few small protests in some Canadian cities: a story in The Province that a Vancouver mob broke windows at the German consulate and tore down the double-headed eagle above the door, and in Montreal a march to the German consulate by a group of French patriots that ended up being canceled due to a heavy downpour.

Most Canadians, however, followed the advice of the Montreal Star’s August 11 editorial to treat Germans with courtesy and consideration: “There are thousands of Germans and Austrians in this country who probably have no intention whatever of abandoning their original desire to become permanent citizens of the Dominion.” In 1911, 5.6% (403,417) of Canada’s population were of German origin, with over 70% working as farm laborers.

On August 7th, 1914 , three days after declaring war, the Canadian Government issued a statement declaring that German immigrants who wish to remain in Canada to continue their business or profession will not be harassed or interfered with unless they engage in espionage, hostile acts, or otherwise break any law, order-in-council, or proclamation.

“Militiamen employed in the protection of public works, buildings, etc. will not hesitate to take effective measures to prevent the perpetration of malicious injury; and should sentries, piquets, or patrols be obliged to use their weapons and open fire, their aim will be directed at and not over the heads of offending parties.”

Among the priorities for the 9,000 active militia on guard duty in August were the protection of vulnerable points, including bridges and railway terminals. In 1914 there were more than 5,000 railway bridges and 4,700 trestles across Canada. Within days of war being declared a large quantity of dynamite – enough to blow up a train – was said to have been found on the track near Parry Sound on the route to Winnipeg. Partly in response to this authorities of the three rail companies announced that armed watchmen would be sworn in to guard the bridges and rail lines. By the end of the week over 600 watchmen had been hired by the CPR.

Despite the deployment of armed watchmen reports of suspicious activities near bridges and rail lines across the country were rampant. The day after the CPR’s announcement an Austrian individual was discovered hiding beneath the CPR bridge in Moose Jaw. He was arrested and brought before a Justice of the Peace but was subsequently released with a fine and a warning about individuals of his nationality loitering near CPR bridges. In Toronto, several tins wired together containing an unidentified black powder were found near a rail bridge; and in Trenton, a rail yard employee reportedly confronted an individual attempting to attach dynamite to the tracks – the suspect escaped, leaving the dynamite by the rails.

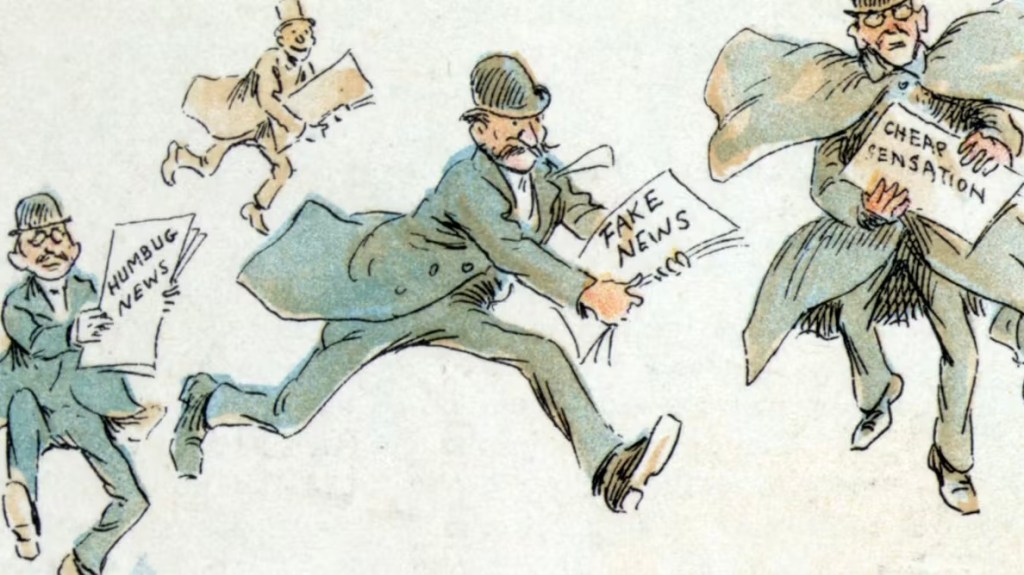

Officials from both the Canadian National Railway (CNR) and the CPR, however, were concerned with the number of “fake” stories being printed by papers. They pointed to a dynamiting in Grimsby, a shooting in East Toronto and bridges being blown up in North Bay, Pickering and Malvern – all of which were untrue and the work of “over-imaginative brains”. The Chief of Police warned the papers that if steps weren’t taken to verify the stories, censors would be appointed who would be empowered to decide which ones could be published.

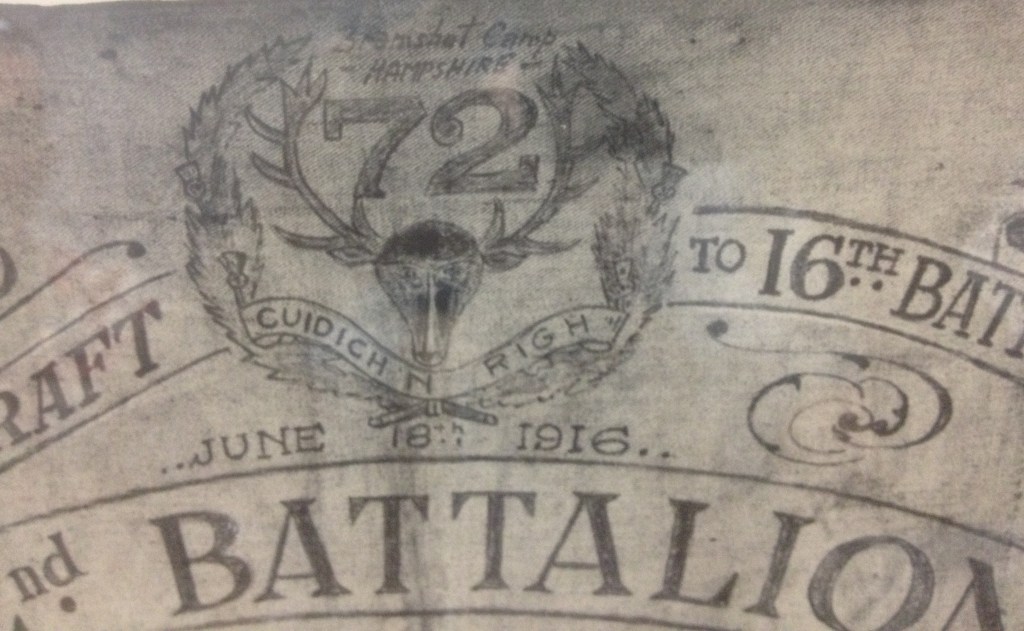

On August 16th, fifty miles from Revelstoke in the interior of British Columbia, six members of Company D, Rocky Mountain Rangers were preparing for the night. A troop train transporting Royal Navy sailors from the Shearwater and Algerine—two old, unprotected gunboats layed up in Esquimalt—to the East Coast to complete the complement of HMCS Niobe was expected in the early hours of the 17th.

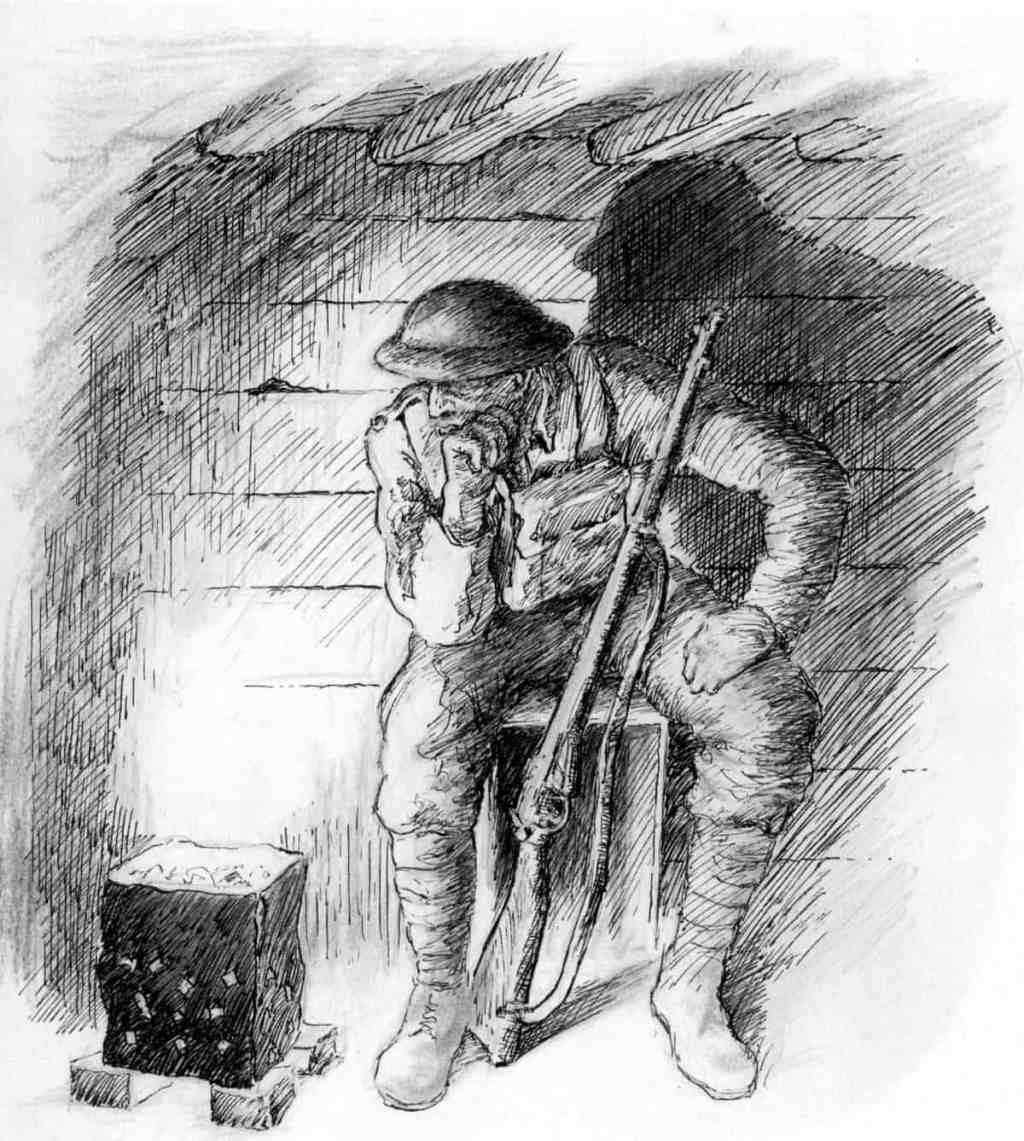

Towards 1am, as a freight train passed over the bridge, Private Alfred Tapping, a fair-haired, twenty year old clerk and native of Revelstoke, one of three guards at the west end of the bridge, heard some movement in the brush. Private William Robinson, another young native of Revelstoke who was also on guard at the west end, responded to the noise with a challenge – it was answered by a rifle shot, followed by three more in quick succession.

A quarter of a mile away, at the eastern end of the bridge, Sergeant Ferguson was leading the second patrol that included Private Phillips and Private Victor Robinson, William Robinson’s younger brother. Hearing gunfire, Private William Dance, the soldier in charge of the three men at the west end, used his lantern to signal forreinforcements. Dance, who had served in South Africa with the Gloucestershire Regiment, had been with the Rangers for a year. Seeing the lantern Ferguson’s patrol immediately headed to help, two bullets narrowly missing Private Phillips as he crossed with the patrol in the dark.

Shortly after the skirmish began the train carrying the sailors enroute to Halifax passed over the bridge unharmed. It bore a white ensign fastened to the rear car.

By dawn the firing had stopped, and the soldiers moved into the bushes to search for the attackers. They had fixed bayonets to probe the dense brush but it was largely impenetrable and the attackers had fled. They did find an old flume – a wooden framed aqueduct used to wash gravel when the bridge was being built – which they guessed was the way the attackers had made their way through the brush and up to the bridge. Newspapers also reported that the next day that a railway worker had seen “men dressing wounds” some distance from the bridge. This was seen to corroborate assertions by the guard that they had hit some of the attackers.

“Revelstoke Sentries Attacked Under Mountain Creek Bridge” was the headline in The Mail Herald on August 19th. The biweekly paper in Revelstoke was the first paper to pick up the story, but it was soon carried in papers across the country: “Tried to Wreck Bridge: Miscreants in B.C. Also Attacked Rocky Mountain Rangers”, read The Berlin News Record; “The Rangers Fired On At Revelstoke” was the headline in Saskatoon’s Star Phoenix; and, “Attack Upon Troop Train From Coast”, in bold letters, in New Brunswick’s Daily Gleaner.

Reports of the skirmish at Mountain Creek Bridge were in line with many of the other stories appearing in papers across the country – stories that increased in magnitude with each telling. But the skirmish was the first account involving the heated exchange of gunfire on Canadian soil, and the story’s detail leant it credibility.

However, the same day that papers were trumpeting the attack, The Province – one of Vancouver’s main dailies along with The Vancouver Sun and The Daily News Advertiser – was reporting that the story was untrue. Under the headline “IT NEVER OCCURRED”, F.W. Peters, general superintendent of the C.P.R and Colonel Duff-Stuart, brigadier in command of the 23rd Infantry Brigade and senior military officer in Vancouver, vigorously denied that the attack had occurred. The two men admonished the papers, saying that “before similar reports are published, the News-Advertiser will at least attempt to consult the military or the railway officials concerned, who would have been able to say that there was absolutely nothing in the story”.

The papers were quick to admit responsibility for the misinformation. They claimed to have published the story in good faith since it came across the wire service, but acknowledged that mistakes will occur under any circumstances.

Nevertheless, they didn’t fail to use it as an opportunity to disparage their competitors. Despite their own culpability in spreading the story, The Vancouver Province pointed fingers at the Sun and the Daily News Advertiser and suggested that had the two newspapers consulted with military or railway officials they would have found that the story was false. The Sun, in turn, accused The Province of shamelessly suggesting that the News Advertiser ran the story knowing full well that it was false. According to The Sun, their competitor knew the story came from a news wire – the Western Associated Press – and would have picked it up themselves had it fit their print run. Instead, “they blacken the reputation of other newspapers when force of circumstances brings about a mistake for which the newspapers are in no way to blame.”

The Sun exacted revenge on the more established Province by pointing out that the story they reported on August 5th concerning the mob that attacked the German Consul was, by its own admission, untrue. Had they checked they would have found that it was consul employees who took down the Eagle under the direction of the Consul General. “As there was more than one man, The Province promptly discovered a Mob”, The Sun quipped.

The response of the CPR and Duff-Stuart showed the mounting frustration among authorities to the proliferation of Fake News that they said created confusion and raised alarm.

The British controlled all war news coming out of Europe and even had extraordinary censorship powers over Canadian newspapers. It was designed to control cables and telegraphs about the war coming from Europe, as well as domestically sensitive military information such as troop movements. These rules would tighten as the War progressed and debate and opposition would increase in kind. The passage of the War Measures Act on August 22nd, for example, put a firm stamp on the Government’s right to impose censorship and control when it deemed a threat to Canada.

The censorship of local news, on the other hand, was voluntarily controlled by the newspapers themselves. In response to a question from the Canadian Press, Sam Hughes, Minister of Militia, pointed out that there is no censorship of land telegraphs within Canada, adding that censorship of the press regarding local news items must be local and voluntary.

For news from abroad, however, newspapers were dependent on news from correspondents and wire copy that was often heavily censored or not forthcoming. Blaming a lack of information and a time lag in receiving stories, newspapers often preferred to feed the public’s frenzy for information, regardless of its veracity. As one Ontario paper reasoned, “the war correspondents grasp eagerly at every rumour they hear, or resort to guessing, hoping therefore to satisfy those for whom they are working. . . If false news is published by the newspapers, the fault is not with the newspapers but with the sensation-loving public that demands news whether or not there is any available.”

Similar to the Vancouver Sun’s defence in printing the Mountain Creek Bridge story, newspapers deflected responsibility and pointed to the wire services and the public’s appetite for news: “It must be perfectly evident to all that there exists a coterie of unscrupulous liars who, in the absence of real news, have been drawing upon their imagination concocting frightful yarns merely for the purpose of catering to the demands for news. . . it is unfortunate that city newspapers have leant themselves to the dissemination of this fake stuff.”

Whether it was the public, the military or the newspapers, in the opening weeks of the War Fake News was a problem that would not go away. It was alarming to the public and an unnecessary drain for authorities. In mid-August Duff-Stuart announced that artillery would be placed in Stanley Park simply for the purpose of allaying the public’s nervousness from the various rumours of the German cruiser Leipzig off the Vancouver coast. Shortly after the artillery was put in place newspapers provided extensive detail of the sinking of the Leipzig, but naval authorities in Esquimalt were quick to deny all knowledge and announced this to be fake.

Denouncing Britain’s censorship of Canadian newspapers Saskatoon’s Star Phoenix suggested that the censorship was “of very dubious quality when it allows the circulation of such alarmist and very obviously false reports . . . if there has to be censorship of news let it be a censorship which protects the people from disquieting stories that have no foundation in fact.”

Natural suspicion, “over imaginative brains” and censorship over the flow of real war news provided the fuel for the rumours and falsehoods in those early weeks. In November the CPR again denied any substance to the rumour of a plot to blow up the Welland Canal and the Hamilton Tunnel: “there have been countless rumours received of activities of Germans, and for some reason Saturdays seem to be the favourite days for these reports.”

That Fake News could influence policy was shown by the government’s response to the shooting of a CPR guard in Smith Falls at the end of the month. First attributed to someone of German descent but quickly determined to be an escaped convict from Kingston Penitentiary, it was enough for Sam Hughes to crack down on potential Austrian and Germans reservists, requesting the Commissioner of Dominion Police to arrest all in the Smith Falls District. It was a precursor to a broader Government Proclamation in October.

As the War moved beyond the opening phase, real news from Europe began to occupy the public’s mind: word of German atrocities crossed the Atlantic, the Canadian contingent arrived in England and the first Canadian was killed at the end of October. On October 29th the first steps were taken towards the internment of Austrian and German residents of Canada. Claiming that the coming winter and the desperately cold weather would compel many of these residents to abandon their law-abiding attitude, the government decided to intern the most dangerous who might leave the country and take up arms in Germany. Taken together, the climate of suspicion at home seemed to slowly change.

The German Secret Service was certainly active in Canada early in the war. Its primary mission was to spread propaganda and conduct sabotage. The Welland Canal, as an example, was a prime target, as the Canadian Government feared. Despite all of the rumours and suggestions of intrigue, however, the first real act of sabotage in Canada didn’t take place until February 1915 with the destruction of the bridge across the Croix River between New Brunswick and Vanceboro Maine.

Fake News is part of the history and lore of the first weeks of the war. In the climate of censorship at the time it’s unclear whether the more elaborate stories, like the skirmish at the Mountain Creek Bridge, the sinking of the Leipzig and the attack on the Hamilton Tunnel, were truly the creation of over imaginative brains or whether their denial and claim as Fake News was a product of censorship.

Over a hundred years after the non-attack, the Skirmish is still remembered in the local BC community, and a celebrated memory of the opening days of the First World War.

Leave a comment