On October 23, 1916, the Victoria Daily Times included what I thought when I first read it was a short, poignant piece involving a soldier, Private Charles Orr, who had recently returned from the Front. As I dug further, however, it struck me that the story of Charles Orr hinted at one of the many challenges faced by the recruitment of the Canadian Expeditionary Force (CEF) and another tragedy in the history of the First World War: men who joined the ranks who may have had undiagnosed mental health issues and could be far more vulnerable to breakdown once at the Front.

The recruitment of men suffering from mental health is an area that has had limited focus in research about the CEF. The majority of research has focused on “shell shock” in the CEF. There were as many as “16,000 men diagnosed with some form of nervous illness during the war, representing about 4% of those who served overseas, or 10 percent of the non-fatally wounded.” * The official estimate is 9,000 men. What doesn’t show in these numbers are those men who had pre-existing mental health issues. Once in the formal military ranks indicators such as repeated discipline issues, in particular AWOL or drunk and disorderly charges, or recurring sick calls and hospital stays, could point to pre-enlistment mental health concerns.

Charles Orr, a private who had served in the 16th Battalion, was convalescing at the Esquimalt Military Convalescent Hospital, having been Struck off Strength and returned to Canada in April, diagnosed with Neurasthenia. For soldiers at the Front neurasthenia was often ascribed to the stress of war – shell shock, or what today might be Post Traumatic Stress Syndrome (PTSD).

While Orr was under treatment at the convalescent hospital he helped to support himself by taking orders for Christmas cards, using his bicycle to cover more ground. Calling on a house one night to deliver an order of cards, he left his bike on the curb. When he returned fifteen minutes later the front wheel had been stolen. The story in the Daily Times was one that would appeal to the public. By the winter of 1916 Canada had suffered more than 45,000 casualties and more than 377,000 had enlisted – over 4.5% of the Canadian population. Every city was affected deeply, and as a major recruiting hub Victoria, and the people of Victoria, would have suffered in kind. Through the story, Orr was appealing for help in returning the missing wheel, as the bicycle was his only means to cover the distance he needed to work.

Yet a story that immediately garnered sympathy for the young, returned soldier, quickly changed.

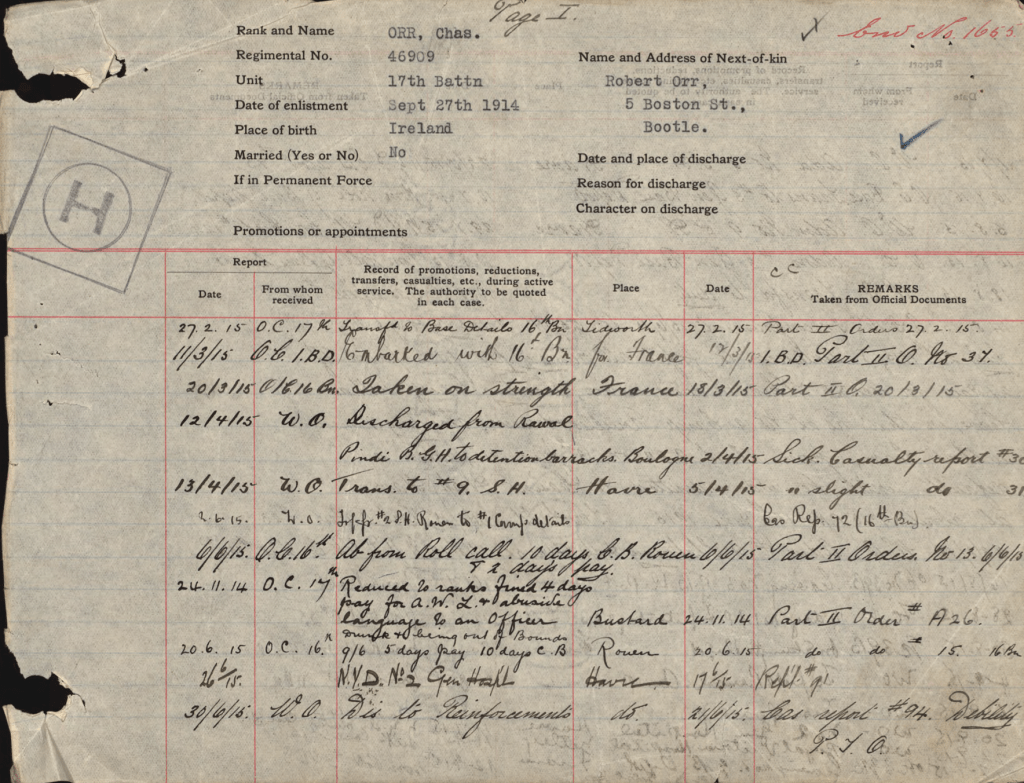

Charles Edmund Orr, a fireman (often factory worker) in Vancouver when the war broke out, enlisted with the 17th Battalion in Valcartier in September 1914, and sailed to France on the S.S. Ruthenia in the first week of October. The Battalion was broken up on arrival in England and in February Orr was transferred to the 16th Battalion, Canadian Scottish, performing base details until he sailed to France with the battalion on 11th March, 1915.

Orr’s service records suggest that he was a troubled young man – quite possibly before he went to France. While his medical history accounts for six months “at the Front” — something quoted repeatedly by multiple doctors — it appears that after his first rotation of 3 days in the trenches he spent most of his time in confinement, in detention, or in hospital, rather than in the trenches.

Orr was Taken on Strength with the Canadian Scottish on 16th March, as part of a draft of forty-six men that arrived over a two-day period. As a move of the 1st Canadian Division had been temporarily cancelled, the Battalion was enjoying a peaceful respite in Estaires, a town about six miles behind the front line.

“Circumstances combine to make the stay at Estaires pleasant. The weather was excellent. The inhabitants were kindly disposed and showed their goodwill in many considerate acts. The town itself was crowded with many British troops and picturesque Indians from the Lahore Division who were billeted in La Gorgue, a suburb of Estaires. There was the music of bands, the skirl of bagpipes, the marching to and from of bodies of men; all the stir and excitement that makes army life at its best so attractive.”

Nevertheless, wastage – the daily attrition from artillery, snipers and other non-battle related casualties – still occurred in the rear. Working parties went out to the trenches, billets were shelled intermittently from a distance and preparations occurred to relieve the 13th Battalion in the trenches, which they did on the evening of 23rd March.

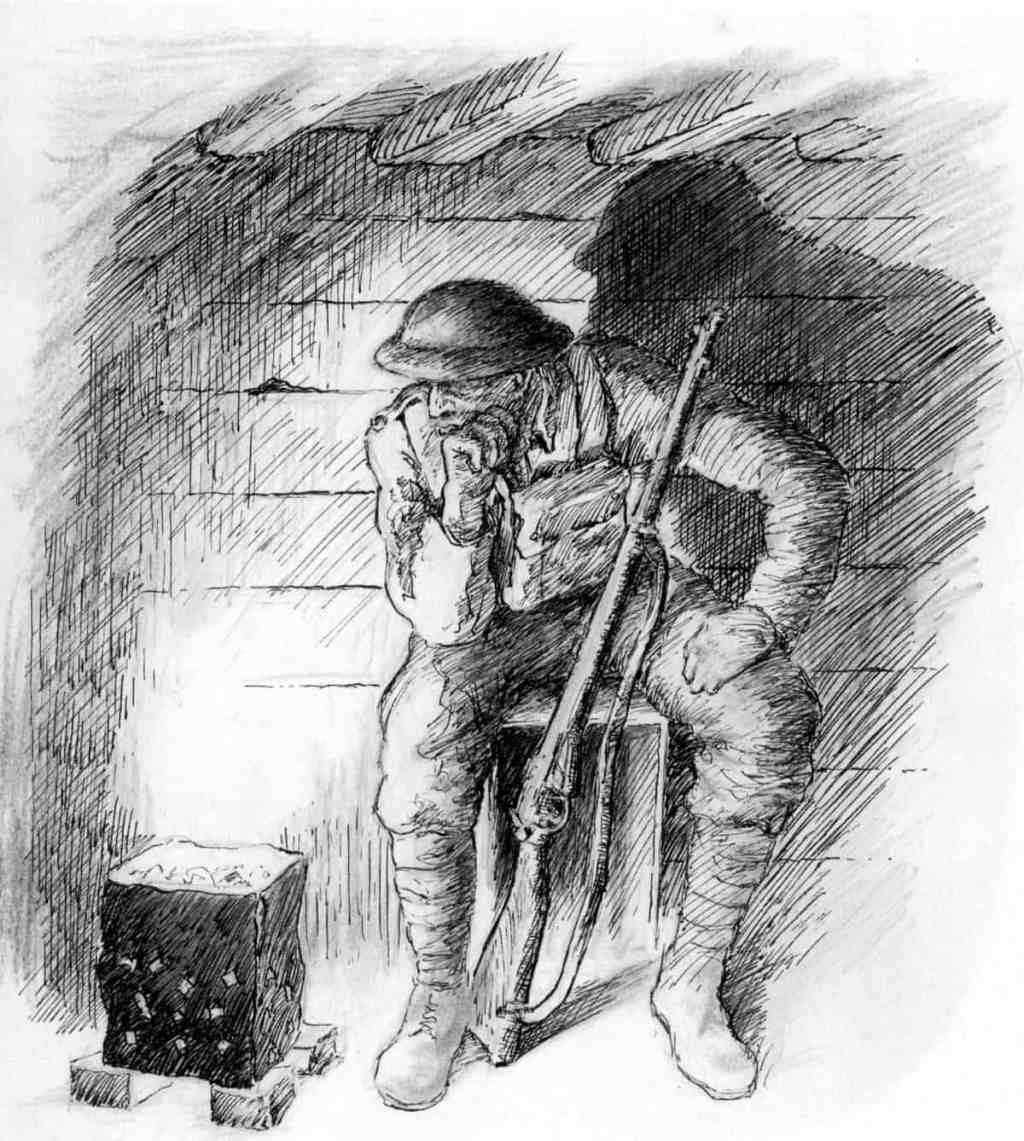

Private Orr’s first stint in the trenches was relatively uneventful. Despite heavy German shelling on the afternoon of the 23rd, there were no casualties over the three day period, so it was simply a matter of suffering the discomforts of the cold and rainy early spring weather and familiarizing the new draftees with trench life. On the evening of the 26th, the Canadian Scottish were relieved by the Northamptonshire Regiment and Sherwood Foresters, and returned to Estaires for six days before embarking on a relatively leisurely twelve day trip north to Ypres. This was a prelude to a momentous event in the history of the Canadian Expeditionary Force, the 16th Battalion, and the war in general: the German attack on St. Julien, the opening of the 2nd Battle of Ypres, and the first use of gas as a weapon in the war.

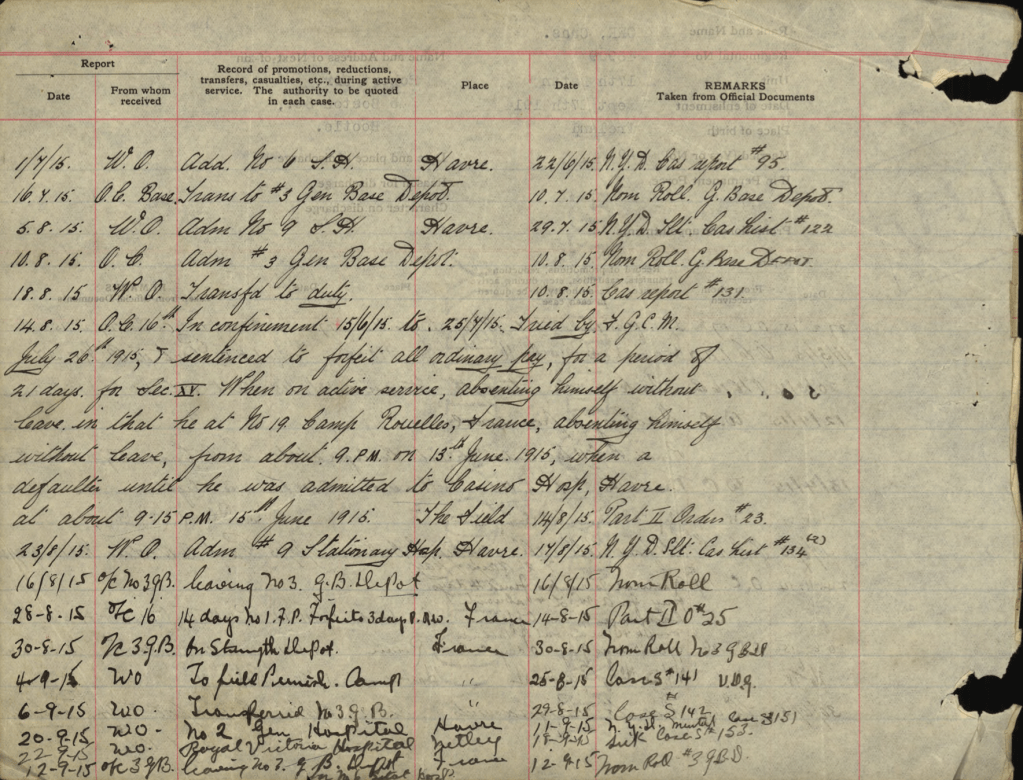

Private Orr, however, was absent from this seismic event in the 16th Battalion’s history – indeed, the history of the First World War – and from much of what followed for the Canadian Scottish. Less than two days out of the line, on March 28th, Orr reported for sick call. After being diagnosed with two venereal infections, he was sent to Rawal Pindi British General Hospital where he was treated and discharged to detention barracks four days later. Over the months of April through August there was a clear pattern of repeated admissions and transfers through hospitals: No. 9 Stationary Hospital in Havre (April 5th); No. 3 Stationary Hospital in Rouen (May 18th); No. 2 General Hospital in Havre (June 17th); No. 6 Stationary Hospital in Havre (June 22nd and again on the 26th); and, No. 9 Stationary Hospital in Havre (July 29th and August 8th).

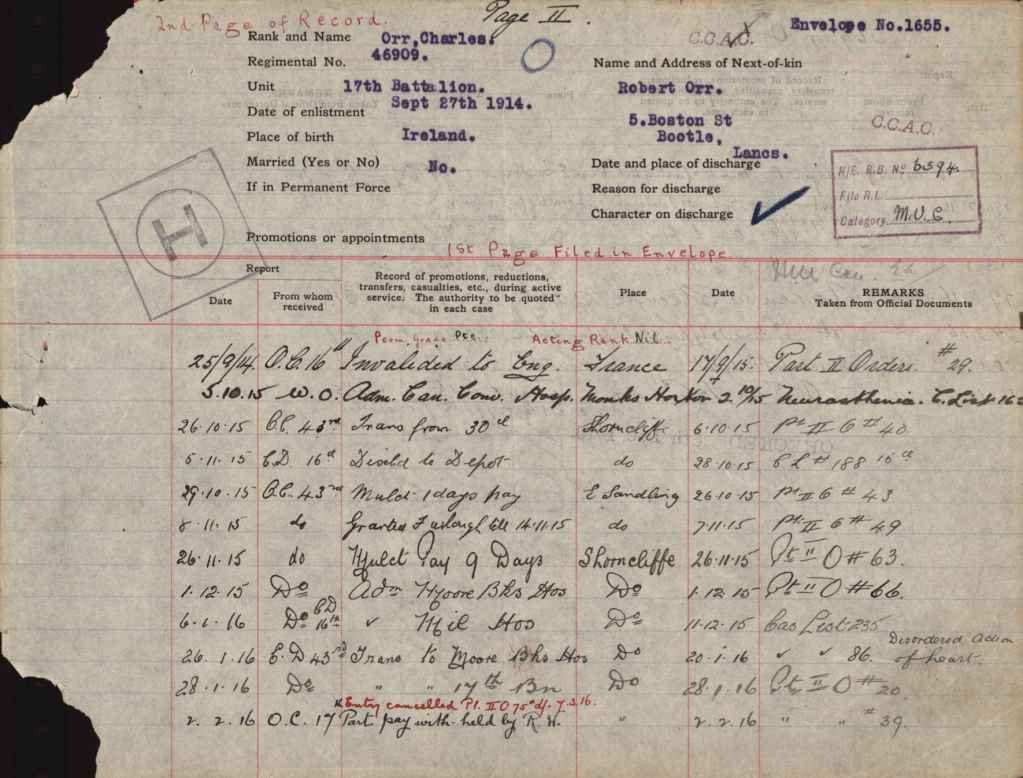

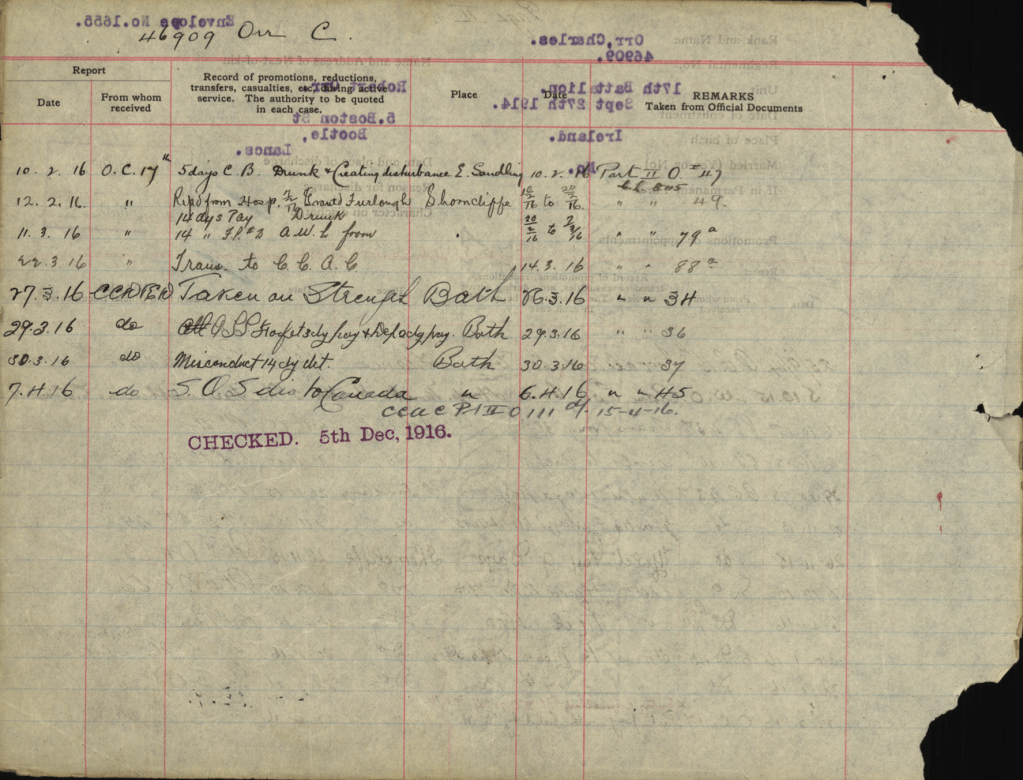

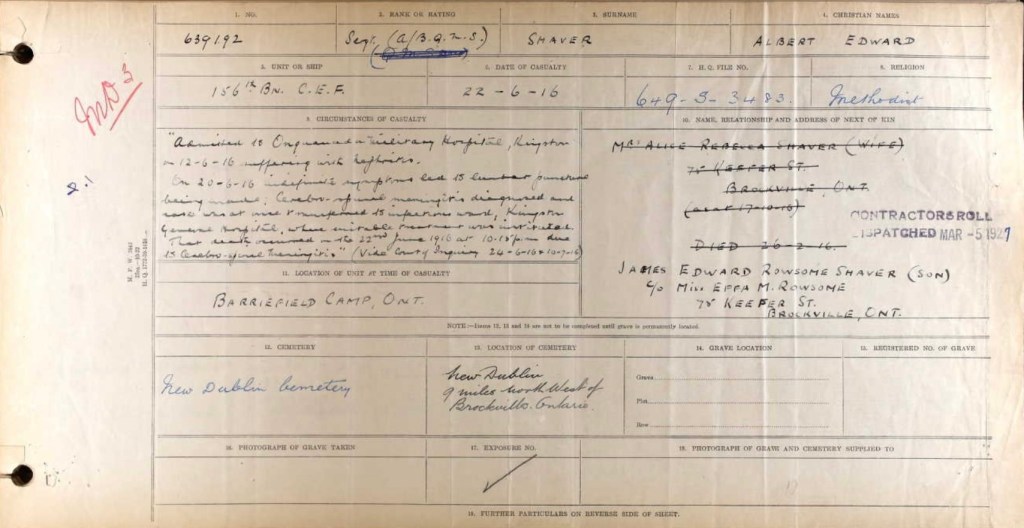

Casualty Forms (Active Record) for Private Charles Orr #46909

Concurrent with Orr’s frequent sick calls was an almost equal pattern of disciplinary infractions: absent from roll call until apprehended by the police (May 26th, 1915); drunk and out of bounds without a pass (June 12th); absent without leave for two days (June 13th); and absent from Tattoo until apprehended by the police (Aug 12th). These incidents continued well into 1916. In addition to confinement in barracks they also led to considerable reductions in pay: the August incident alone led to the loss of 65 days of pay.

In isolation, these may have appeared simply as disciplinary failures. However, in the context of his medical record it appears more complicated. One medical officer noted: “No. 46909, Pte Orr C, 16 Canadian Inf, has been under observation here since 22/6/15. I understand . . . that his defence is that he suffers from loss of memory. According to him he had two drinks at the camp on the day in question & remembered no more until he was found by the police and taken to the hospital.” The doctor’s report, dated July 7th, 1915, went on to record additional claims of alcohol-induced memory loss, aligning with recorded infractions for absenteeism. While the medical report concluded that “he is not in any way insane,” it did suggest that he had “wandered into town without quite knowing what he was doing.”

On September 11th, 1915 Orr was again in the No. 2 General Hospital in Havre. This time, instead of the casualty report reporting N.Y.D – Not Yet Diagnosed – the diagnosis was “mental”, and a week later he was admitted to the Royal Victoria Hospital at Netley, a vast, sprawling Victorian institution on the south coast of England and one of the primary receiving hospitals for wounded soldiers. Significantly in Orr’s case, it also included a specialized psychiatric unit – an emerging area devoted to the care and treatment of neurological cases coming from the Front. During his sixteen days at Netley Orr was diagnosed for the first time with Neurasthenia; a condition noted in numerous medical reports that followed. From that point, his epitome of hospital treatment in England showed a steady movement through institutions:

18 September 1915 – The Royal Victoria, Netley;

2 October, 1915 – Monks Horton Convalescent;

6 October, 1915 – Canadian Convalescent, Epsom;

11 December, 1915 – Shorncliffe Military Hospital;

January 1, 1916 – Moore Barracks, Shorncliffe (convalescent);

February 18, 1916 – Military Palm Grove, Birkenhead;

Military Shorncliffe.

A postcard showing the Royal Victoria Hospital at Netley during the War

In December 1915, Orr was recommended for invaliding to Canada. He finally returned on the S.S. Metagama in April, 1916 and was referred for treatment in Esquilmalt. While undergoing this treatment Orr was recommended for discharge as medically unfit; he was granted a pension for six months and discharged, and was allowed to convalesce in his own home.

On discharge, a medical report noted that, “he is nervous and has attacks of tremors and palpitation upon excitement. Occasionally under such conditions he becomes semi-conscious, but does not fall.” The report concluded that his debilitated condition was due to previous service and described a marked disability.

Yet Orr’s relatively limited period of front-line exposure raises questions about whether military service was the real cause, or whether this front line service merely exacerbated underlying vulnerabilities that were already present before enlistment.

In a medical report a year later the neurologist, reported:

“There is still some mental disturbance, as manifested by the fact that he has difficulty focusing his attention, consequently has a bad memory and he is easily confused by the slightest excitement.”

Charles Orr’s life after his return to Canada appeared to have continued the pattern witnessed overseas — or perhaps it revealed patterns that had existed before the war. Within a year of returning home, a series of legal troubles emerged for which he was charged twice with assault. In each incident, Orr received a suspended sentence owing to his nervous condition as a returned soldier. He was charged again in March 1923 for misappropriating money from the sale of tickets for the Ladies’ Auxiliary of the General Hospital, and again a number of years later for a minor theft; in all cases he escaped with a suspended sentence.

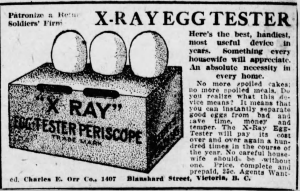

In addition to his efforts selling Christmas cards, Orr tried his luck representing U.S. companies through a series of dubious business ventures, not uncommon for the time, advertising new “household devices” that promised miraculous results to make life easier. Among them was a butter maker that claimed to produce eight pounds of butter from one gallon of milk — a scientifically impossible claim — and an X-ray Egg Tester Periscope that promised to “. . . instantly separate good ones from bad and save time, money, and temper.” In advertising the Egg Tester, Orr casually added the tagline “Patronize a Returned Soldiers’ Firm.” While the Egg Tester escaped official scrutiny, he was not so lucky with the Butter Maker, finding himself before a magistrate in August 1917 for “publishing an advertisement containing false statements.” Orr had sold 100 of the devices, making a profit of $1 per machine — which the magistrate claimed as “practical robbery in cases of persons who were easily duped by absurd statements.” Again, Orr received a suspended sentence, with a warning to discontinue the practice.

It was during court proceedings over the breakdown of Orr’s marriage in December 1924 and January 1925, however, that a darker pattern of his behaviour emerged. Orr married Lillian Ebba Fernland in 1919 when she was sixteen but the marriage broke down amid allegations of his drunken abuse and infidelity — facts that came to light before a magistrate in July 1924 when Lillian sought and was granted a separation from her husband. Lillian was also given custody of their four-year old son.

Two months later Orr was arrested after trying to kidnap his son, allegedly hiring someone to steal him while he was alone at a store buying candy with money his father had given him. During more formal divorce proceedings in front of a magistrate in December, it also came to light that Orr was in the habit of feeding whiskey to the child.

In court proceedings in December/January confirming an earlier decree of divorce it emerged that Orr had attempted to mislead the court by paying someone to lie on his behalf about an affair. The judge upheld the earlier decision, finding Orr had “molested” his wife, committed adultery and abuse.

Through the 1920’s Orr continued to have his challenges with the law — charged on several occasions with assault, theft and drunkenness.

On 15 August,1930 six lines in The Province (Vancouver), was all that was told about the short life of Charles Edmund Orr — a man who enlisted to fight in the First World War, who struggled through the machinery of the war’s medical administration, and returned home to build his life:

Orr – passed away in this city Aug. 12, 1930, Ex-Private Charles Orr, 17th Infantry Battalion, age 40 years. Funeral Services in Hanna’s chapel Saturday morning, Aug 16 at 10:30 o’clock. Internment Returned Soldiers plot, Mountain View Cemetery.

The Victoria Daily Times story that had first caught my attention introduced a young soldier trying to recover from injuries sustained in the War and wronged in a way that would appeal to local sympathy. Yet a closer examination of Charles Orr — through his service record and subsequent confrontations with the law — reveals a far more complicated individual than initially portrayed.

The First World War marked a turning point in the understanding and treatment of psychological trauma, then commonly described as shell shock. Early in the conflict many sufferers were viewed as malingerers or cowards — men thought to be shirking their responsibilities or lacking the nerve to do their duty. Over time, however, specialized institutions such as the Royal Victoria Hospital at Netley, with its dedicated psychiatric unit, and Craiglockhart War Hospital — made famous by the treatment of poets Siegfried Sassoon and Wilfred Owen — began to reshape perceptions, framing psychological trauma as a medical condition.

Yet what of those who entered service and already suffering from mental health issues. Their enlistment in the CEF may have exacerbated an underlying condition through exposure to stress and entry into a medical system pre-disposed to attribute such trauma to front line service.

I am not a medical professional so any discussion of mental health is tentative. Charles Orr’s story, however, illustrates the way in which a potentially troubled individual struggled within a system that was itself just beginning to understand a very complex new field of war injury.

* Tim Cook, Shock Troops 2007.

Leave a comment